New Catheter Removal Protocol Reduces CAUTIs

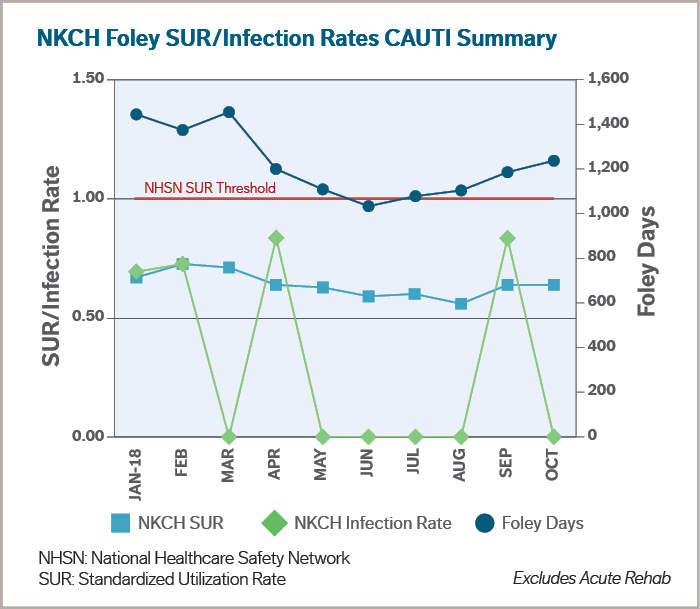

January 1, 2019A new protocol at North Kansas City Hospital reduces catheter-associated urinary tract infections, the fourth most common hospital-acquired infection, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. From May-October 2018, NKCH achieved a 13% reduction in Foley catheter use and a 75% decrease in CAUTIs (see graph).

CAUTIs

Nationally, between 15-25% of hospitalized patients, opens new tab receive urinary catheters. Yet, prolonged catheter use is the most common cause of CAUTIs. Each day an inpatient’s indwelling urinary catheter remains, the risk of acquiring bacteriuria increases 3-7%, opens new tab, notes the CDC. “CAUTI risk increases steadily with each day, so the clock is ticking from the minute a catheter is used,” said Mary C. O’Connor, MD, opens new tab, medical director of NKCH’s epidemiology and infectious disease control program and an infectious disease specialist with Metro Infectious Disease Consultants, opens new tab.

Indwelling Catheters: Reasons for Medical Necessity

Urinary catheters are deemed medically necessary for:

- Accurate intake and output in a critically ill patient is essential and a bedpan, commode, external catheter or urinal is not conducive to patient care

- Urinary retention, including obstruction and neurogenic bladder, and the patient is unable to pass urine due to blood clots, edematous scrotum/penis, an enlarged prostate or side effects cause by neurological disease/medication

- Short perioperative use in selective surgeries (less than 24 hours) and for urological studies or surgery on contiguous structures

- Assist in healing of open perineal and sacral wounds in incontinent patients to avoid further deterioration of wound and skin

- Required immobilization for trauma or surgery

- Hospice/comfort care or palliative care if requested by the patient or family

- A chronic indwelling urinary catheter on admission (may clarify reason of use from physician)

CAUTIs increase the risk of morbidity and mortality. “When a patient gets a bad urinary tract infection in the hospital, they often get mentally confused,” said Dr. O’Connor, who also chairs NKCH’s infection control committee. “Their kidneys may not work well, and they can become septic. This delays a patient’s recovery and can increase their length of stay. All of this will improve with the new protocol.”

Nurse-Driven

The protocol empowers nurses to evaluate a patient’s need for an indwelling urinary catheter and remove it promptly when it is no longer medically necessary. The protocol requires:

- Urinary catheters are inserted only when medically necessary

- A physician must order a catheter

- Each shift evaluate and document the medical necessity for the catheter

- Urinary catheters not be used for convenience

- Urinary catheters not be inserted to monitor output with the exception of intensive care units, where hourly output is necessary for hemodynamic monitoring

It stands to reason that because nurses are on the frontline of patient care, they should have such autonomy. “Nurses are the critical bedside piece in the care of our patients,” Dr. O’Connor said. “They spend the entire day with the patient. They are doing critical thinking on a minute-by-minute basis. They have the most opportunity to intervene with the patient and reduce the risk of infection. Physicians aren’t at the bedside as long as nurses, and their priority is to address critical issues of the day.”

Infection preventionists round throughout the hospital to help bedside nurses understand the need for applying the protocol. They educate nurses about catheter alternatives, including using bedpans, commodes, external male or female catheters, and straight intermittent catheterizations.

Nursing documentation keeps physicians informed. Each day, the patient’s electronic medical record prompts the attending physician to document the continued need for an indwelling catheter. There are two exceptions to the protocol. The catheter cannot be removed without a discussion with the physician if: 1) the patient is being treated with urology or genitourinary services; and/or 2) if the patient had surgery involving the urinary tract or any contiguous structures.

“My patients have been receptive,” Dr. O’Connor said. “Female patients have remarked on the comfort level of external catheters and that they provide more mobility. Additionally, they know they are being taken care of without being put at increased risk for infection.”

Mary C. O’Connor, MD

Mary C. O’Connor, MD

Dr. O’Connor, opens new tab earned her medical degree from the Medical College of Wisconsin, where she completed her internal medicine residency. She was an infectious disease fellow at the University of Kansas.